Biography

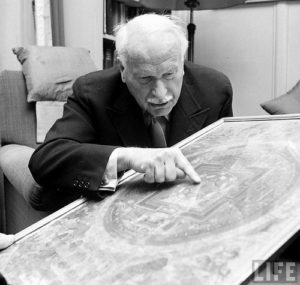

Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961), Swiss physician, psychiatrist and founder of Analytical Psychology, was one of the great explorers of the inner world we call psyche. Many of Jung’s ideas have entered mainstream thought and influence how we think about ourselves today.

Jung began his professional life treating patients and conducting scientific research at the Burghölzli Clinic of the University of Switzerland in Zürich, then the most famous psychiatric hospital in Europe. He was already prominent in his field when he read Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams. Jung wrote to Freud, suggesting his research might provide scientific corroboration of Freud’s theories of the unconscious. The two men met in 1906 and began an intense collaboration to map unconscious realms.

Their relationship ended in 1913 as Jung developed psychological theories that diverged from Freud’s. Simply put, Freud’s theories, rooted in sexuality, were based on the premise that the unconscious was mainly a repository for repressed experience. As Jung deepened his theoretical explorations, he realized that universal mythological themes arise in dreams and fantasies in humans throughout the world. They arise out of the unconscious and are experienced as the wellspring of creativity and growth. Jung later understood the universal themes as archetypes that affect how we live, think and feel.

The break with Freud precipitated a six-year period of personal crisis that Jung came to call his confrontation with the unconscious. Jung chronicled this period in a richly illustrated volume called the Red Book, only recently published. His experience became the foundation for a lifetime’s work that embraced wide-ranging studies, writing, travel and teaching. Jung’s theory and method, analytical psychology, mapped human dynamics in their complexity and depth.

Growth, individuation, and psychological development

The goal of psychoanalysis is to help a patient to grow into the individual he has the potential to be. Jung named this process of personal growth “individuation”. In his autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Jung explained, “I have frequently seen people become neurotic when they content themselves with inadequate or wrong answers to the questions of life. They seek position, marriage, reputation, outward success or money, and remain unhappy and neurotic even when they have attained what they were seeking. Such people are usually contained within too narrow a spiritual horizon. Their life has not sufficient content, sufficient meaning. If they are enabled to develop into more spacious personalities, the neurosis generally disappears. For that reason the idea of development was always of the highest importance to me”.

“There is no illness that is not at the same time an unsuccessful attempt at a cure.”

The Unconscious and Archetypes

The methods that Jung developed to initiate and sustain the analytic process require that we establish a creative relationship with the personal unconscious and the collective or transpersonal unconscious. Our personal unconscious contains the forgotten or unintegrated residue of our individual history. The collective unconscious comprises universal archetypes common to all cultures throughout human history. Jung defined archetypes as primordial patterns inherent in the psyche. Unknowable in themselves, they manifest as compelling images and motifs. Archetypal images take a variety of forms, including inner personalities Jung designated as shadow, anima, animus and the Self. A few representative examples of archetypes include:

Personalized figures: the wise old man, the witch, the trickster, the hero, the divine child, the hero, the wise old woman.

Objects: trees, magical rings, swords, gems, The Holy Grail.

Places: home, enchanted gardens, hell, labyrinths, caves.

Processes: night sea journeys, rites of initiation, heroic quests, and alchemical procedures.

Abstract forms: circles, squares, spirals, and mandalas.

These and other similar universal patterns generate autonomous psychic energy that can undermine us if we don’t find a way to consciously relate to them. Relating to the psychic energy within the therapeutic process leads to increased consciousness that, in turn, allows us to channel that energy for personal growth.

Jung discovered that his patients not only deepened self-knowledge, but also shed outworn, confining attitudes and actively aspired to and achieved new, more creative and fulfilling lives. Symbolic images can serve as helpful guides on the journey of self-discovery, but contemporary culture often loses touch with the wisdom they embody–a wisdom that was once familiar to older cultures through their myths and rituals.

“My work as a psychoanalyst is to help patients recover their lost wholeness and to strengthen the psyche so it can resist future dismemberment.“

Innovations and contributions

Today, many of Jung’s innovations are familiar and have been absorbed into mainstream thinking. Many have been independently affirmed by other schools of therapy and analysis.

One of Jung’s most significant early clinical insights is the recognition that the therapeutic relationship not only involves but also affects both the analyst and patient. He underscored the role of the analyst’s own personality and participation in the work, and recommended that all analysts undergo their own extensive analysis as a prerequisite to professional practice.

Jung formulated “complex” theory. Today, in popular parlance, when someone is acting emotionally or is “out of sorts”, we say he or she is in a “complex”. Jung visualized complexes as the building blocks that structure the psyche. His theory of complexes enabled him to understand how certain unconscious thematic groups of feelings and ideas powerfully impact our everyday lives. At the core of every complex is an archetype around which our personal life experience forms a shell of emotional experience.

The Association Test is an experimental procedure used to gather information on a subject’s unconscious processes. The test administrator provides the patient a word to which the patient verbalizes an immediate response. A series of words are introduced and each is responded to until, at the end, a psychological pattern emerges. Today, the association test is still used in a variety of settings and has, in fact, formed the basis for the “lie-detector” test.

Jung’s theory of psychological types provides the theoretical foundation for assessment tests in use today. The most widely known is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Jung’s theory distinguishes between introverted and extroverted orientations, with four additional psychological functions: thinking, feeling, intuition and sensation. The Myers-Briggs is in use today in a variety of contexts to help clarify personal strengths, life choices (such as vocation or relationships), and corporate group dynamics within the workplace.

Jung also pioneered many well-known expressive clinical techniques to “dream the dream onward”. The practice he called active imagination encourages patients to draw on energy generated within a psychoanalytic relationship to create fantasies, paint pictures, sculpt forms in clay, write poems and stories, dance or move the body expressively, or construct scenes in sand trays in order to foster a relationship with the unconscious. Creative therapeutic practices have generated particular therapeutic modalities, such as art therapy, movement therapy, drama therapy (psycho-drama) and role-playing.

Jung devoted his life to the study of psyche. His living legacy, Analytical Psychology, enables us to discover–-as he did–-that the mind is one of the “most mysterious regions of our experience” and that there is “no end to what can be learned in this field”.